Gods in Chinese Religions

The Buddha

Earthenware plaque carved with the Buddha flanked by two bodhisattvas (enlightened beings), H. 13.3 cm, W. 9.8 cm, 7th century A.D., Shaanxi province, China.

Buddhism, originally from present-day India and Nepal, was transmitted to China during the first to second centuries A.D. and flourished since the fifth century. Despite its various schools of thought and teachings, its main figure, the Buddha, was widely worshipped as the enlightened one who not only gave wisdom for this life, but also guided people for good rebirth. Represented here on this plaque is the Buddha’s peaceful posture on a lotus seat under a sacred fig tree, a symbol of enlightenment.

Guanyin

Porcelain figure of Guanyin, H. 46.3 cm, W. 14.5 cm, early 17th century A.D., Dehua, Fujian province, China.

British Museum 1980,0728.290. Shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.

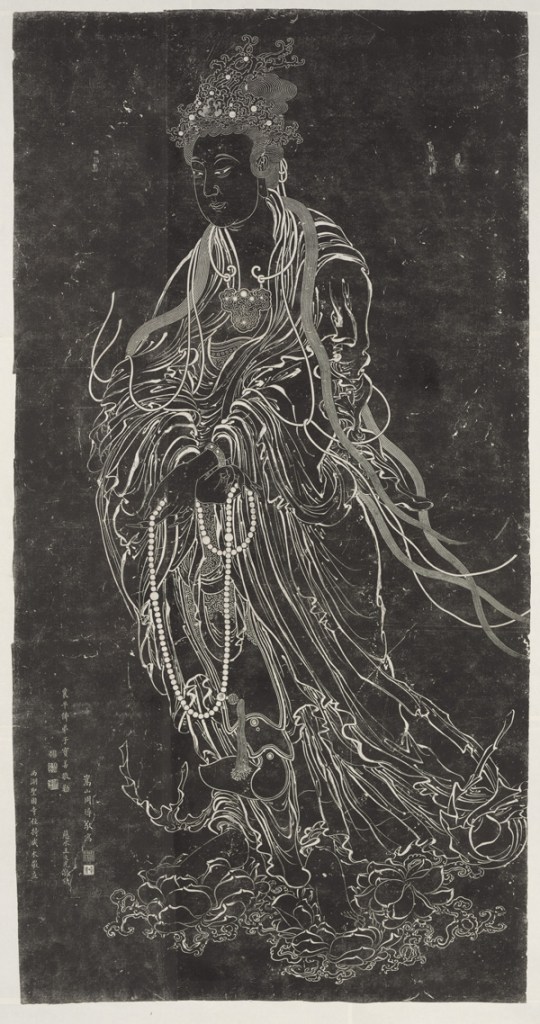

Rubbing of a stone carving of Guanyin, ink on paper, H. 190.5 cm, W. 106.7 cm, stone carved during the late 17th to early 18th centuries A.D., rubbing made in the 20th century, China.

Guanyin (meaning ‘hearing all voices’) is a Chinese adaptation of an Indian bodhisattva (a person ready to become a Buddha but remaining in this world out of compassion). Unlike the enlightening Buddha, Guanyin mostly provides divine assistance and saving to individuals. From around the tenth century onwards, Guanyin was worshipped as a Goddess of Mercy. She was accredited with a wide range of abilities, such as healing, granting offspring, relief from famines, and military assistance. Both representations here feature the goddess appearing on auspicious clouds with a benevolent expression. The porcelain figure on the left shows one of her usual images of wearing a white robe, whereas the rubbing of a stone carving shows her aloft by clouds enroute to rescue humans.

The True Warrior

Ceramic figure of the Daoist god True Warrior (Zhenwu), H. 45.7 cm, W. 25.7 cm, D. 10.8 cm, 15th century A.D., Cizhou, China.

Apart from Buddhist deities, there were many indigenous gods in Chinese religions. The True Warrior (Zhenwu) was one of the most widely worshipped Daoist gods. As the personification of the direction of the north, which symbolised military action and defence, the god was revered for protecting the household, the imperial family, and the empire. The god is represented in a military image here, wearing a brightly decorated robe and accompanied by his symbols of a tortoise and a snake (in the middle). The ceramic figure was probably used for veneration on a home altar.

Confucius

Bronze figure of Confucius seated on a chair, H. 49 cm, made in 1652, China.

British Museum 1963,1216.1. Shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.

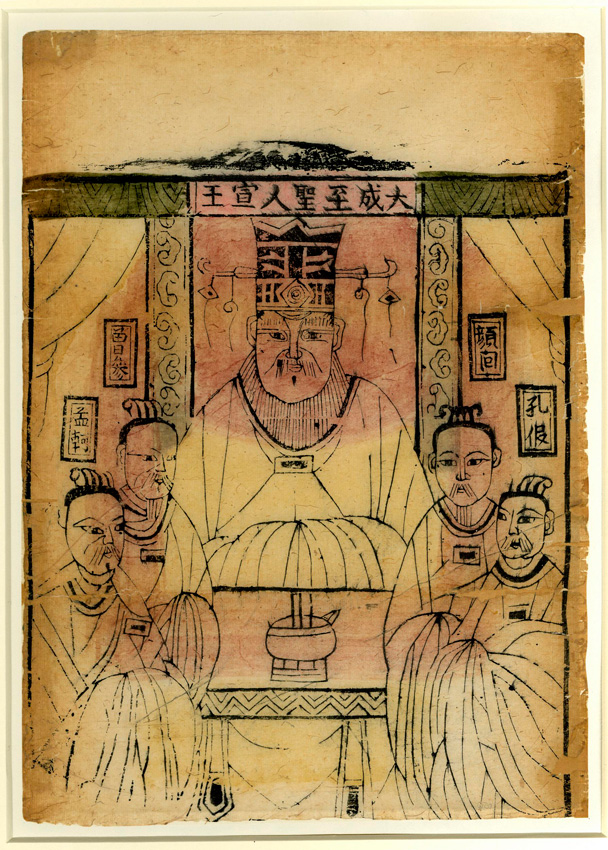

Woodblock print of Confucius and four disciples, ink and colour on paper, L. 31 cm, W. 25.50 cm, 20th century A.D. Beijing, China.

British Museum 1982,1217,0.50. Shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.

As the most revered sage of antiquity, Confucius was worshipped by men of literature and learning. Men preparing for civil service examinations would not only immerse themselves in the sage’s teachings but would also pray to him in Temples to Confucius. The bronze figure on the left captures Confucius’ character of civility and propriety, whereas the woodblock print on the right portrays him as a solemn and awe-inspiring sage. There is a minor mistake in the title of this decorative print: the third character from the left should be ‘wen’ (literature), here mistaken as ‘ren’ (person). The mistake nevertheless suggests the god’s popularity among commoners who wish for an official career for their sons.

Thunder Gods

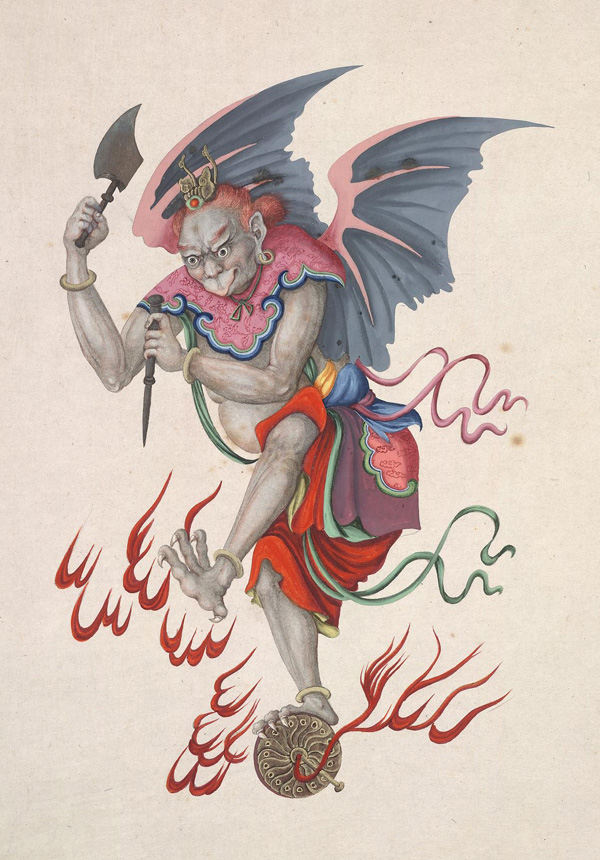

Painting of the Thunder God on an album leaf, H. 45.7 cm, W.36.8 cm, c. 1801-1850, China.

British Museum 1877,0714,0.1333-1337. Shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.

Thunder Gods probably originated from people’s fear of lightning in nature. Yet in Chinese religions, they were closely associated with morality. As gods in charge of administering punishment from Heaven, they were perhaps more feared than revered. Here is a portrait of a Thunder God, Leigong, who emerged in the Tang dynasty (seventh to early tenth centuries A.D.). He is portrayed as an airborne creature in human form with a bird’s beaks, wings, and claws. The axe and chisel in his hands are especially awe-striking and are symbolic of his power to punish those who violate moral rules, no matter how well they hide.

Goddess of Privy

Image of the Goddess of Lavatory, imprint, late 16th century, Nanjing, China.

Unknown author, Expanded Records of Seeking the Gods, New Edition with Portraits 新刻出像增補搜神記, Fuchuntang imprint, Nanjing, late 16th century A.D., China.

The Goddess of Privy was one of the deities who protected people in their most private spaces and moments. She was a deified woman with a tragic story: a literate and brilliant young lady married to a prefectural governor as a concubine in 687 A.D., she was murdered by the governor’s wife out of jealousy and her body was abandoned in a privy. After death, she manifested her power in telling fortunes through the ritual of spirit-writing. Also known as the Purple Maiden in the twelfth century, the goddess seems to have undergone major changes in nature that resulted in her contradictory roles in popular religion. On the one hand, she assisted people with her literary and prophetic abilities, yet on the other, she took on the role of a guardian of the loo.