Chinese gods were believed to have the power to save people from life-threatening dangers and other urgencies in life. A variety of sources – such as official records, local gazetteers, inscriptions, anecdotes, and private writings – included accounts of divine saving. The areas of divine intervention ranged widely: for individuals, issues regarding health, safety, and livelihood were among the most frequently reported. Gods could heal deadly diseases, protect a person or a household from dangers such as murder, robbery, riots or warfare, animal attacks and other accidental deaths. The safety of merchants and envoys in seafaring and that of women during childbirth were also major areas of need. For communities and states, divine powers were often sought for rain or stopping rain, expelling locusts from the fields, healing people from plagues, and defending a city or a state from bandits, rebels or invaders.

The power of gods to save was well acknowledged in Chinese religions. Some gods had the word ‘save’ (jiu 救) in their titles. A good example was the Heavenly Worthy of Supreme Unity Who Saves from Suffering 太乙救苦天尊, a popular Daoist saviour god who saves suffering dead souls. The word ‘save’ was also part of the title of Guanyin, a widely worshipped Buddhist goddess. In other Chinese cults, when the gods received a title from the state, sometimes it would contain the character ji 濟, literally, ‘to ferry’, ‘to sail’, and metaphorically, ‘to rescue’, ‘to aid’. The following source texts, ranging from the 12th to 16th centuries, provide glimpses into the powers of five gods or goddesses in saving people from dangerous or difficult situations.

1. 1

Battles and droughts

宋孝宗淳熙十年癸卯,福建都巡檢羌特立奉命征剿溫州、台州二府草寇。官舟既集,賊船蟻[聚?]水面,眾甚懼。方相持之際,咸祝曰:『海谷神靈,惟神女夫人威靈顯赫,乞垂庇護』。隱隱見神立雲端,軿蓋輝煌,旗幡飛飆,儼然閃電流虹。賊大駭。俄而我師乘風騰流,賊舟在右,急撥棹衝擊之,獲賊首,並擒其黨,餘䑸四散奔潰,奏凱而歸。

宋光宗紹熙元年庚戌夏,大旱,萬姓號呼載道。神示夢於郡邑長曰:『旱魃為虐,我為君為民請命於天,某日甲子當雨』。及期,果銀竹紛飛,金飆噴澍,焦林起潤,暵穀生春。

Translated text: In the tenth year of the Chunxi period (1183), a guimao year, 1 under Emperor Xiaozong’s reign during the Song dynasty, Qiang Teli, the Chief Military Inspector of Fujian, was appointed to lead an expedition to suppress bandits in the two prefectures of Wenzhou and Taizhou. Once the official ships were assembled, the bandits’ ships also gathered on water in large numbers. The crew [on the official ships] were afraid. During a moment of stalemate, they prayed together: “Among all gods and spirits of the deep ocean, only the Divine Lady2 has shown the greatest power and efficacy. Please save us!” In a blurry view, there stood the goddess on top of the clouds. Her carriage and canopy were gorgeous. Her flags were waving wildly as lightning struck furiously. The bandits were frightened. At that moment, our troops were able to advance in smooth winds over currents. The bandits were on our right-hand side. So, we suddenly changed our direction and launched attacks on them. We captured the chief bandit and caught his gang. As the rest of their ships fled in every direction, we returned in victory.

In the summer of the first year (1190), a gengxu year, of the Shaoxi reign of Emperor Guangzong during the Song dynasty, there was a great drought. Tens of thousands of households wailed along the roads. The goddess appeared in the dreams of the administrators of prefectures and counties, telling them: “The drought demon is causing harm. I shall plead with Heaven3 on behalf of you and the people. On the jiazi day there will be rain.” When the day came, heavy rain poured and great winds blew as expected. Forests and crops that had almost dried up started to moisten and return to life.

Source: Records of the Heavenly Consort Manifesting Divine Power 天妃顯聖錄, first compiled around the 1620s by Lin Yaoyu 林堯俞 (a retired official from the Ministry of Rites in the late Ming dynasty), reprint in Taiwan wenxian congkan 台灣文獻叢刊 (Collection of Documents in Taiwan), Taibei, 1960, vol. 77, p. 29.

1. 2 Farming and irrigation

制曰:朕念金華地多高仰,以潴蓄水,三十六堰居多焉。乃睠爾神,曩常俶載,惠顧不忘,迨今沿溢,洪濟穡事,田畯歌之。爰命有司,載申徽號,其祗服休命無斁。嘉定十年丁丑二月十六日下。

Translated text: The imperial order: “I [the emperor] consider that the lands of Jinhua mostly consist of high ground. Water storage in reservoirs is mostly achieved through the 36 weirs there. I appreciate that the god started these weirs4 in the past and has given blessings ever since. The weirs are still in use today to irrigate crops, for which peasants sing their praises. I therefore ordered ministers in charge5 to arrange the conferment of a fine title. May the god fulfil the appointment without fail.” Issued on the 26th day of the second month in the tenth year, a dingchou year, of the Jiading reign (1217).

Source: ‘Song Ningzong feng Guangjiwang gao’ 宋寧宗封廣濟王誥 (Imperial Order of Enfeoffment as the King of Broad Relief by the Ningzong Emperor of the Song Dynasty), in Zhaolimiao zhi 昭利廟誌 (Records of the Temple of Manifest Benefits), compiled by Du Xiangfeng 杜翔鳳 in the first half of the 17th century, reprint in Zhongguo daoguanzhi congkan xubian 中國道觀志叢刊續編 (Collections of Daoist Temple Records in China, Continued), vol. 15, p. 28.

1. 3 Dangers at sea

廣州城南五里,有崇福無極夫人廟,碧瓦朱甍,廟貌雄壯,南船往來,無不乞靈於此。廟之後宮繪畫夫人梳裝之像,如鸞鏡、鳳釵、龍巾、象櫛、牀帳、衣服、金銀器皿、珠玉異寶,堆積滿前,皆海商所獻,各有庫藏收掌。凡販海之人,能就廟祈筊,許以錢本借貸者,縱遇風濤而不害,獲利亦不貲。廟有出納二庫掌之。船有遇風險者,遙呼告神,若有火輪到船旋繞,縱險亦不必憂。凡過廟禱祈者,無不各生敬心。

Translated text: Five li (one li was about a third of a mile) to the south of the city of Guangzhou,6 there is the Temple of the Lady of Limitless Lofty Blessings. The temple looks magnificent with green tiles and red pillars. Ships engaging in trade in the southern sea that pass by would all stop for the crew to pray here for the goddess’ numinous protection. The hind palace of the temple has a portrait of the Lady grooming and dressing. Piled in front of the portrait are numerous things such as mirrors decorated with patterns of phoenixes, hairpins in the shape of phoenixes, turbans embroidered with patterns of dragons, combs made of ivory, curtains and clothing, gold and silver vessels, and precious beads and jades, all presented by maritime merchants. Each item is kept in the inventories of temple treasuries. For the merchants who do business on the sea, if they can visit the temple to pray or cast moon blocks7 and promise capital for loans,8 even if they encounter wild winds and waves, there will be no harm. They can even make a big profit. There are two treasuries in the temple that administer cash in and out. When a ship encounters danger on the sea and calls from a distance for the goddess’ help, if wheels of fire come to whirl around the ship, then there is nothing to worry about even though it is in danger. For this, those who pass by and pray at the temple will all show reverence.

Source: ‘Chongfu Furen shenbing’ 崇福夫人神兵 (Divine soldiers of the Lady of Lofty Blessings), in Huhai xinwen Yijian xuzhi 湖海新聞夷堅續志 (Sequel to the Record of the Listener: New Stories from across Lakes and Seas), unknown author of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1367), reprint Beijing: Zhuhua shuju, 2006, p. 213.

1. 4 Dangers from a landslide

(華蓋) 山近地名七富,有一鄉民,偶忘姓氏,累世奉祀三仙。紹興間,忽然山崩,俗諺謂之山嘯,所居前後左右同時崩摧。一家同聲誦大仙聖號求救,四簷之外盡爲深坑,獨一家如在高臺之上,更無餘地。因以全活,自後遷基,其地亦壞。

Translated text: Close to the Huagai Mountain9 there was a place called Qifu, where a villager lived. His name has been forgotten. His family had worshipped the three immortals10 for generations. During the Shaoxing period (1131-1162), there was a sudden landslide, known by custom as ‘a mountain’s roar.’ As the land surrounding his house was collapsing and sinking, the whole family chanted the great immortals’ epithets11 together and pleaded to be saved. The land in the four directions beyond the eaves of their house all turned into deep pits. Only their house stood there as if built on an elevated platform. No other land remained. They then survived. Later the foundation of the house was relocated elsewhere, and that land also collapsed.

Source: ‘Song shenghao mian shanbeng yasi’ 誦聖號免山崩壓死 (Chanting the gods’ epithet and escaping being crashed by a landslide), in Huagaishan Fuqiu Wang Guo sanzhenjun shishi 華蓋山浮丘王郭三眞君事實 (Factual Records of the Three Transcendent Lords of Huagai Mountain: Fuqiu, Wang, and Guo), compiled in 1261 and revised during the 14th century, reprint in the Daoist Canon 道藏 of 1445 (no. 778), 5.15a.

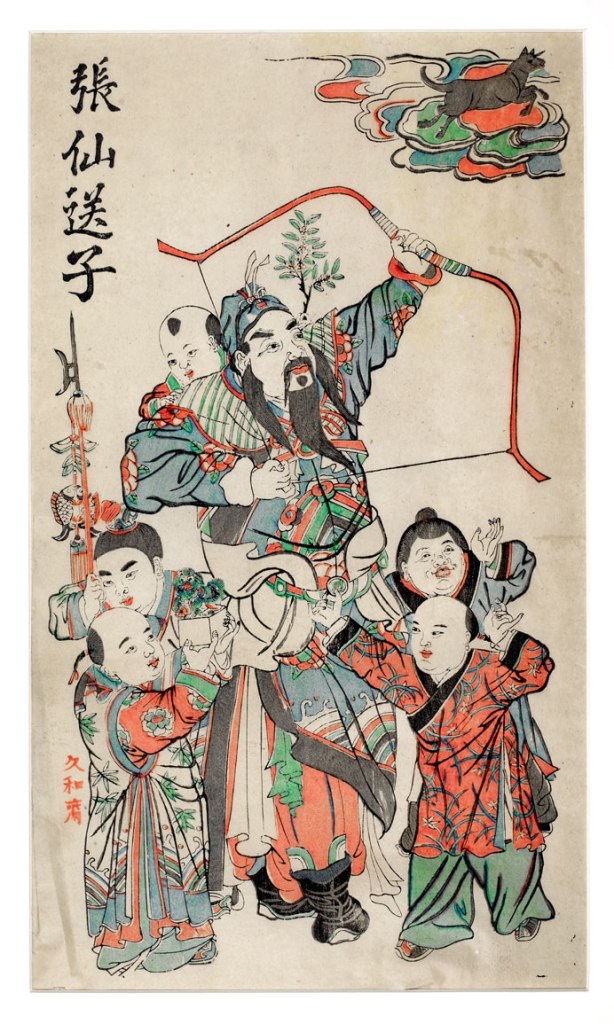

1. 5 Giving offsprings

(…) 五嶽並尊,獨東嶽為世所崇奉,東嶽諸神,又獨天仙聖母為世所崇奉,豈非以東方生物之府而萬物皆生於母耶?西直門外高梁橋,舊有天仙祠,都人士求福澤利益者嵗無虛日,而祈嗣者尤眾。田子尚禮年旦(且)五十四歲,無嗣,躬禱於神,願力行善事,以祈神佑。又恐志之弗堅,言之或渝也,伐石於山,立之祠前,以表貞堅不易之意。(…)

Translated text: The Five Peaks12 are regarded as equally noble, yet only the Eastern Peak is venerated by all in this world. Among the various gods of the Eastern Peak, again only the Heavenly Immortal Sage Mother13 is venerated by all in this world. Isn’t it due to the fact that the east14 is the place for generating things and that the ten thousand things are all generated from their mothers? At the Gaoliang Bridge outside the Xizhi Gate (of Beijing), there used to be a Shrine of the Heavenly Immortal. Everyday there were people in the capital who went there to pray for blessings and profits. Those who went to pray for offspring 15 were especially many. Mister Tian Shangli, approaching the age of 54, had no sons. He prayed to the goddess in person and made a vow to do good with full effort so as to obtain divine assistance. But he worried that his resolution was not firm enough and that his vows might fail. He quarried a slab of stone from the mountain and established it in front of the shrine to express his unswerving will. (…)

Source: ‘Tianxian shengmu ganying beiji’ 天仙聖母感應碑記 (Record on Stele of Responses from the Heavenly Immortal Sage Mother), written by Yu Jideng 余繼登 in 1599, in Beijing tushuguan cang Zhongguo lidai shike taben huibian 北京圖書館藏中國歷代石刻拓本匯編 (Compilation of Stelae Rubbings throughout Chinese Dynasties in the Collection of Beijing Library), Zhengzhou, 1989, vol. 58, inscription no. 5827.

Notes:

- guimao, also gengxu and jiazi below: numbers within a cycle of sixty used together with emperors’ reign titles to mark the years in imperial China. ↩︎

- Divine Lady: the goddess was a deified human named Lin Mo’niang living in the tenth century. She was later known as Mazu (Mother Ancestor) or by her various other titles, such as the Heavenly Consort or Heavenly Empress. ↩︎

- plead with Heaven: for communal disasters such as drought that were supposed to be punishment from Heaven, the goddess was to act as an intermediary rather than saving people directly. ↩︎

- the god started these weirs: the god was said to have been when alive a military commander named Lu Wentai 盧文臺 in the first century AD who led his troops in building public irrigation works. ↩︎

- ministers in charge: referring to officials in the Ministry of Rites, which administered ceremonies, sacrifices, and title conferment to both human officials and gods. ↩︎

- Guangzhou (Canton): a major port city on China’s south coast since the seventh century. ↩︎

- moon blocks: a pair of wooden or bamboo pieces used for divination in a temple or at a family shrine by throwing them on the ground. ↩︎

- capital for loans: it suggests that the temple also engaged in money-lending activities. ↩︎

- Huagai Mountain: a sacred site in Jiangxi, south China, known for Daoist immortals. ↩︎

- the three immortals: the Three Transcendent Lords of Huagai Mountain named Fuqiu, Wang, and Guo. ↩︎

- chant epithet: a popular way of invoking a god’s assistance in various Chinese cults. ↩︎

- Five Peaks: the five most important mountains on Chinese territory, i.e. Mounts Tai, Hua, Song, Heng in the four cardinal directions, and Song in the middle. Mount Tai was also known as the Eastern Peak. ↩︎

- Heavenly Immortal Sage Mother: sometimes also known as the Jade Maiden. ↩︎

- the east: had the symbolic meaning of birth and growth in Chinese cosmology. ↩︎

- pray for offspring: particularly sons to carry on the family line. ↩︎